Something in the Way

Using Kurt Cobain's diaries as a blueprint for understanding vocal dissociation

On and off throughout life, I’ve taken vocal lessons. They started in school, a series of pitch-seeking scales matched to a Steinway piano. In adolescence they continued with the choir lady at church, a compact, energetic woman with a blonde bob who wore sweeping, floor-length dresses the color of dark wine. She had an affinity for Andrew Lloyd Webber and Appalachian hymns. To this day, phrases of these hymns repeat in my mind. These dregs of memory swirl up when I sit down to write melody:

didn’t my lord deliver Daniel

you better get on your knees and pray

down in the river to pray

And, lately, the funeral chorus:

will the circle be unbroken?

As an adult I took lessons from a retired opera singer in recovery from alcoholism. Her dark humor put me at ease. I laughed. My shoulders dropped. I opened myself to her method, which transformed the way I felt my neck, lungs, the abductor muscles connecting my ribs. She encouraged me to feel the grit and gristle of my body. For the first time I became aware of my breath as it passed through me, vibrated my water, blood, and bones.

Vocalists are always calling their body an instrument, but this feels self-objectifying, an over-compensation for being taken less seriously than the guy picking arpeggios on guitar. If your body is an instrument, anyone can play it. Pick it up. Puppet the strings. Such porous boundaries never work for me.

⥈

On social media I watch thirty second excepts of singers performing for the iPhone camera. Many of them lip sync because it sounds more produced. Their voices ring like polished silver. The sounds of the body—the high-hat click of consonants, the note where one transitions from chest to head voice, cracks—are smoothed out.

I have made 30 second excerpts. Set up the ring light. Bored myself with the process. Again, who’s playing this thing? Not me, I realized, watching a video of myself. So who then?

Or What?

Was it the pressure to prove my own productivity? That leftover neurosis gifted by a well meaning but perfectionistic father? Or could it be the compulsive anxiety manufactured by a culture that over-values industriousness?

Whatever it was, I wanted it out. I burned ritual candles, told it to fuck off. Only then could I ask myself what I wanted to invite in.

Look, I said, I got this body latent with environmental cancers. This raw patch in the throat. All these bones weak from not enough milk as a child—and so much rage and lust you could break a chain with it, swallow the sun.

⥈

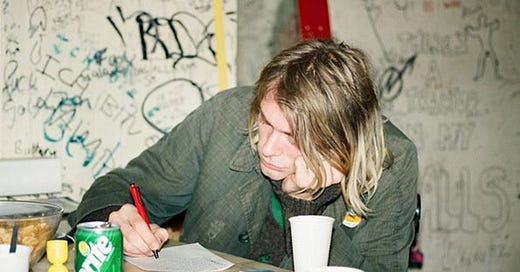

I am overly conscious of the sincerity in my voice, wrote Kurt Cobain in a diary entry. These words appear in a bulleted list of what seem to be hard truths the singer was trying to come to terms with in himself. Also on the list:

I am threatened by ridicule.

I like to have sex with people.

I understand and appreciate religion for I understand my emotions are affected by music.

I use bits and pieces of others personalities to form my own.

When I was taking lessons with the opera singer, she said that for people like me and her, the most important part of vocal training wasn’t adding to the voice, but stripping it down. Anxious people can get caught in complexes, perform what we perceive others demand from us. We forget our power, the spirit of our breath, which is always with us and will never leave until the day it leaves us forever, and we will ascend, descend, or rot sideways into the earth.

That Cobain struggled to feel at home in his voice is no surprise. The man carried trauma like a stone in his stomach. Self-medicating through heroin, he became an escape artist to his body. Dissociated from his core, he screamed from his chest.

Cobain’s diaries were a formative text for my artistic development. I don’t idolize rock stars for the simple reason that idolizing them kills them. What I feel for Cobain is the bond of a kindred spirit, a fellow journeyman on the path to the home all of us are always seeking—the home that might be a myth, with all its power, weight, and radiant impossibility.

Cobain’s diaries portray a man who struggled mightily to grasp the impact of his life. He protected this struggle with rage-fueled screeds against patriarchy, capitalism, and inauthenticity.

He wrote of Aberdeen, his hometown of pain and love, the fusion of which he sung into cheap tape recorders. Reading scanned pages of Cobain’s raw, scratched handwriting, I saw a bridge span across the decades and artistic styles that divided us. I felt called to trace the impact of my experiences on my voice.

⥈

It starts here:

They are smearing mud in my hair. I am seven years old, and the blonde boys are smearing mud in my hair.

The tall, blonde, angular boys have bones like regurgitated car parts. Angels of beat summer, they walk with monstrous swagger. Their smiles—and they are smiling, now, as they keep smearing mud in my hair—are pink and pockmarked.

The blonde boys don’t like me. They don’t like their mothers, either, or their teachers. They don’t understand girls or women, or death, which they believe happens only to girls and women. I’ve seen the blonde boys tempting death, riding bikes into heavy traffic, or swiping at the webs of brown recluse spiders. I’ve seen them squeeze lit fireworks. Drink amber cough syrup. Drink anything at all.

The only people the blonde boys respect are their fathers, but this is a coerced respect, born of fear. Their fathers return home slamming doors, speak in gruff voices, and the blonde boys stiffen, shoulders hunched.

Last week, a blonde boy was my friend. We played Nintendo and drank Mountain Dew from plastic cups while his parents fought in the kitchen. This week, he avoids my eyes.

It is because their fathers discard them that the blonde boys are smearing mud in my hair. At seven years old, I have learned this much about blonde boys and the graves they dig for their spurned tenderness. The mud at the bottom of those graves is dark, wet, and clumped with grass. Sometimes it contains the bones of a fish. Sometimes it contains a seed.

A soft rain hovers over the street, empty but for the blonde boys, the mud, and my body, which I am both in and observing from above. I have become a split witness to myself : I breathe, blink, and bite my lip, but my spirit is not there. My spirit—my breath—is up in the air.

Remembering my spirit in this moment, I recall the movie Thelma & Louise. “Something’s crossed over in me,” says the actress Genna Davis in her portrayal of Thelma. “I can’t go back.” She says this before driving her car over the lip of the Grand Canyon. With this act of suicide, she escapes the police, the blonde boys in their patrol cars chasing her 1966 blue Ford Thunderbird.

One imagines the Thunderbird crushed against the dry rock. There would be an explosion. A crimped plume of smoke. Two bodies in the wreckage. Before gravity dragged Thelma and her friend Louise–holding her hand in a double suicide pact–down to their dead end–there must have been a moment–just before the nose of the car began to dip–that felt like flying.

⥈

The breathlessness of dissociation stayed with me, informed my voice. I can struggle grounding the pillar of air within me. The opera singer assigned me breathing exercises to build tolerance for the presence of air, the awareness of my diaphragm. They work if I work them.

⥈

It keeps going:

Becoming a split witness to myself among the blonde boys, I feel the weightlessness of flight. I am seven years old. I do not know how to divide a fraction. I do not know a street bigger than this narrow lane in western Pennsylvania. But I can survive. I can split my spirit from my body. In this way I can avoid complete humiliation.

But I don’t want to avoid it. I want to fight, get even. But I’m afraid to fight. So I run to the apartment of a friend of my older sister, to tell her what happened. My sister’s friend answers the door in a towel. She smells of patchouli and lavender. She looks like a woman in a soap commercial. I am aware of the dirt weighing down my eyelashes. My sister’s friend suddenly seems too beautiful, too clean for me to speak with. What would she know of mud?

I hate the blonde boys, their asphalt politics of fear, their love frustrated to hate. Wiping my eyes, my skin feels granular.

To this day the grit textures my voice, fuses with vowels, especially i.

What was I wearing that day? Twenty years later, why do I think this detail matters?

They are smearing mud in my hair.

We use the passive voice, a teacher once told me, when we want to separate ourselves from an event legally, socially, or emotionally.

The event is childhood. The event is a state of victimhood accompanied by the overwhelming desire to escape. Something’s crossed over in me.

There is the voice, and there is the passive voice, a vaporous distance. It is crossing. Over. It is splitting. Its witness.

An excerpt from Kurt Cobain’s suicide note:

I’m too sensitive. I need to be slightly numb in order to regain the enthusiasms of my childhood.

Reflecting on childhood, many people remember a formative humiliation. Left unexamined and unprocessed, this humiliation can progress to chronic shame. Kurt continued:

I have it good, very good, and I’m grateful, but since the age of seven, I’ve become hateful towards all humans in general.

We look at the world once, in childhood, wrote the poet Louise Glück. The rest is memory.

Preparing for death at age twenty-seven, Kurt addressed his suicide note to Boddah, his childhood imaginary friend. To Boddah, the note begins. Speaking from the tongue of an experienced simpleton who obviously would rather be an emasculated, infantile complain-ee. This note should be pretty easy to understand.

Emasculated. Infantile. What Kurt shared in his final moments was no fleeting humiliation, but it’s chronic, progressive remnant: shame. Faced with humiliation, a child might aggressively cut the mud from her hair, yanking to feel the pain she believes she deserves. Faced with chronic and progressive shame, an adult might load a gun.

Or, if loading a gun feels too final, too violent a gesture, an adult may work his way up to the act by injecting heroin. Kurt did both, dying by a self-inflicted bullet wound shortly after leaving a rehabilitation facility.

The paradoxical tragedy of the opiate is that the drug ultimately produces the opposite of its desired effect: once a user stops taking a painkiller, they experience more pain than before. As the drug wears off, the body overcompensates in an attempt to establish equilibrium. Compound pain floods the neurons.

The painkiller becomes a killing pain.

As a young adult, I worked in a campus crisis center. There, I helped people like Kurt Cobain unload the literal and metaphorical guns. I often conducted CAMS Suicide assessments, which ask clients to distinguish between physical and psychological pain. I never found this categorization helpful. Spiritually, with conscious effort, we might make this distinction, but our neurons cannot. To the soft, throbbing flora in our skull, pain is pain.

In addition to the psychological pain of his final hours, Cobain suffered from chronic intestinal pain and bronchitis. The flora of his skull must have felt on fire.

Cobain wrote music addressing that fire. Something in the way, he sang about his sense of trapped isolation. Something in the way. Listening to his long echo, one gets the sense that the singer believes he is in the way.

In a documentary Montage of Heck, Kurt’s mother shares a story of her son as a child reacting to a recording of his voice. In a shock of excitement, Kurt names his echo Boddah. Boddah, his imaginary friend, was present for Cobain’s first song, just as he was present for his last breath. No one escapes the persistence of childhood; some of us, with luck, integrate and accept it.

Failing the developmental task of integration, we cannot cross the threshold to the next stage of life. If we do not cross the threshold, we cannot grow; and if we cannot grow, we may find it increasingly difficult to count ourselves among the living.

The ghost of childhood like a fish bone gets stuck in the throat, causing immense pain. It changes the sound of a voice. Shutters the air.

Something in the way, Kurt sang on the couch with his 12-string Stella acoustic, five nylon strings he never tuned.

Something’s crossed over in me, said Thelma at the edge of the Grand Canyon, cornered by earth, sky, and blonde boys.

Something will never be the same, I thought at seven years old, sliding mud from my hair. Something is gone forever.